After I tweeted about my recent post about Immunium, another Twitter user made me aware of iCancer. Why? – Because the clinical trial financed through the iCancer fundraising campaign used the Ad5PTDf35-adenovirus vector which Immunicum includes as one of their treatment platforms under development.

What is iCancer?

The campaign group iCancer was founded in 2012 in order to crowdfund a clinical trial in neuroendocrine tumour patients with the above-mentioned adenovirus vector. It all started when Alexander Masters, a professional writer, was desperate to help find a cure for his best friend. Together with some other organisers who Masters met early on in this venture, he organised the campaign, raised the needed money for the trial and developed a novel concept for future trial funding.

In my previous article I didn’t really look at the adenovirus vector. So, let’s have a wee peek before exploring the iCancer initiative and its potential future implications.

Who or what is AdVince?

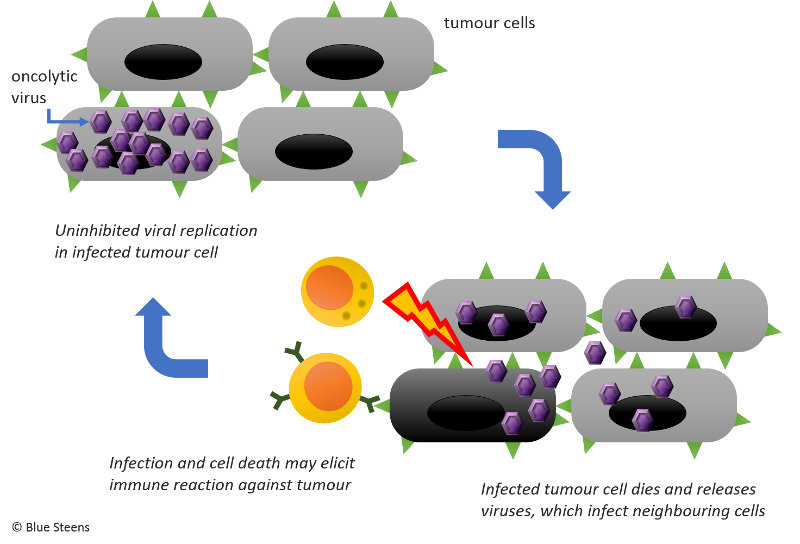

Since 2008 Professor Magnus Essand and fellow scientists at Uppsala University had been working on a genetically modified oncolytic adenovirus, a virus that can destroy cancer cells (see illustration). More specifically, they had tested it on neuroendocrine tumours in mice with promising results. Then they stored it in a freezer. That’s the “Ad”.

The biggest donor in the iCancer campaign who donated 2M Swiss Francs was the late Vince Hamilton. Himself a cancer patient, the millionaire’s top-up of all the other smaller donations made the trial possible. That’s the “Vince”.

The phase I/IIa clinical trial using the oncolytic AdVince in neuroendocrine cancer patients started in spring 2016. Follow updates on the Oncolytic Virus Fund website or the iCancer Facebook page.

Why are promising treatments not developed further?

You might wonder why it took a random guy’s (Masters) initiative to kick off a clinical trial when the potential treatment had already proven promising in the lab.

There are several reasons why many treatments never make it from bench to bedside (beside the fact that some turn out to be unsuitable for human therapy). As is the case with neuroendocrine tumours, some diseases are so rare and difficult to treat that it is simply not financially viable for a company to invest into drug development. You can’t blame them. The patient target population might be so small that they’d never even make their money back on time before patent expiry when cheaper generics flood the market. Alternatively, the treatment would have to be crazy expensive and unaffordable for any public health service or regular earners, never mind poor people.

The above point presumes that there is a patentable compound or tool. If the treatment comes out of the academic realm, there might not even be that. This was the case with the AdVince vector. Professor Essand had already published scientific articles about it because that’s what academics must do to gain credibility in their field and rake in funding. This makes it very difficult for any interested company to find ways to patent the treatment. Nevertheless, Immunicum has managed somehow.

Another problem is that some drugs are useful for a variety of diseases, but some markets are simply more lucrative than others. Thus, drugs are not sold for certain indications and reserved for more profitable ones. This is something that bugs me greatly. But again, it’s the numbers that matter. How fast will the company make their investment back and start turning a profit? The good news is that a drug may eventually be approved for additional indications once the price is driven down by market forces. This scenario doesn’t apply to AdVince just now, but it could easily happen to this or other virus-based therapies.

We’ll see whether AdVince gains a wider application spectrum if it turns out successful in this initial human trial. Theoretically, AdVince or modified versions of it could be applied to other tumours or even other types of diseases, maybe more prevalent ones which would make it more commercially appealing.

Making the AdVince trial happen

Because AdVince was so unattractive to industry at the time, there was no way for Professor Essand to secure enough funding to run a clinical trial. The current AdVince trial was only possible because around 2000 individuals donated money which build up a crucial initial fund and lent the campaign the needed credibility as well as publicity.

Thereafter, one much needed generous donation by a millionaire made it all happen. With his donation Hamilton bought himself a chance to participate in the trial that, he hoped, could save his life. Sadly, he died before the trial even started; so did Masters’ friend. Hamilton’s donation remained invested though. That was part of the deal. Through his donation other patients could enlist in the trial for free. Basically, Hamilton paid for himself and everybody else.

Treatments for the rich? Is this moral?

At first glance, people may criticise the idea that a rich person can buy their way into an experimental treatment. But that is a shallow viewpoint. In essence, the rich person makes the trial possible in the first place and also finances the participation of other trial participants.

The fundamental societal problem already exists. Rich people can afford better healthcare. They can afford more expensive health insurance, fancy spas and clinics, private psychologists, personal trainers, physiotherapists, carers and so on. This inequality already exists. The beauty of the iCancer idea is that other patients benefitted at the same time, patients who would otherwise not have had any access to the experimental treatment at all. Besides, who are we fooling? Health is a business. As much as we want it to be socially responsible and equally available to all, it is not. I do actually think that the iCancer approach addressed this inequality in an effective and practical way in its niche of rare diseases. After all, who else would pay? Would it not be immoral to neglect a potential cure when there is a way to fund it? Could a treatment for rare diseases eventually grow into a treatment for common diseases?

Another argument could be that the idea exploits the desperation of a rich patient. It preys on their misfortune to get some money out of them for the promise of a chance for a better future … well, a future altogether. This is true, but it is true for so many other things we all buy. That’s how marketing works, isn’t it? The iCancer approach gives a rich patient otherwise unavailable access to a potentially life-saving cure. If they believe in the treatment’s potential and are ready to be a guinea pig, why wouldn’t they invest?

That’s how I see it – as an investment. The rich person has too much money to consume, so they invest anyway in commodities, stocks or property in the hope of getting value back in the form of money. Here, the rich person invests spare cash in a treatment in the hope of getting value back in the form of time or quality of life. When you have so much money that you can purchase almost anything, these gains are worth more than money. As with any investment there is a risk involved when investing in an experimental treatment. – It might not work. It might come too late for you. It might make your condition worse. An investor knows that and bases their decision on the estimated risk.

The plutocratic proposal

Masters and his team have thought a lot about potential questions surrounding the ethics, legality as well as medical and commercial worth of the iCancer approach. They have started working with the Uehiro Centre for Practical Ethics at the University of Oxford. Even more impressively, Masters has developed a plutocratic proposal to generalise the concept applied in the AdVince trial campaign. By the way, the dictionary says a plutocrat is “someone who becomes powerful because they are rich”.

There is an excellent 2014 article with accompanying audio recording of Masters’ journey to develop the plutocratic proposal. Since you’ve read this far, you will want to explore that. Seriously, take the time. The one-hour SoundCloud audio is embedded below. Find the written version and a link to iTunes here.

The initial central idea was that a match-maker, the “Dating Agency”, facilitates the information exchange via a website between scientists ready to trial a treatment and potential donors and participants. On top of that, the agency could offer a scientific monitoring committee that verifies the quality of submitted projects, advice on a donor-driven independent peer-review process, a discussion forum for donors and scientists and other helpful features to assist the process.

Along the journey, Masters met insiders who helped him develop the idea further by ironing out ethical, legal and commercial concerns. The article is so insightful and filled with information, that I felt overwhelmed. So, I tried to list the salient points:

- The Dating Agency should be a charitable or other non-profit body. Besides the gain in trust, running this Agency as a charity may bring additional benefits such as tax-efficient donations.

- The Dating Agency’s board and the ethics committee should include patient reps in addition to the usual suspects (e.g. ethicists, doctors).

- The Dating Agency basically sells trial tickets to plutocrats. This right of trial access can be used by the donors themselves, or they can transfer it to somebody else.

- Forced beneficence is critical to the scheme. The wealthy donor must pay for poorer patients.

- The system must not be abused by a rich donor to fudge study criteria to include or exclude patients at will or dictate the Agency’s agenda.

- Funded trials must be phase I or IIa trials to avoid that the rich donor ends up in the control group (e.g. placebo) through randomised allocation.

- Alternatively, trials with control groups must offer compassionate usage exemption (i.e. exclusion from randomisation in favour of receiving the treatment) to the rich donor and other patients whose participation is financed by the donor.

- If the drug works but does not eradicate the disease during the trial period, the rich donor must finance ongoing access to the drug for themselves and the other participants for up to 2 years even if the treatment didn’t help the donor, but benefitted other trial participants. Other funding sources will be determined during these 2 years to push the drug further.

- The Dating Agency receives the drug from the supplier and passes it on to the usage exempt patient.

- The physicians of patients enrolled through compassionate usage exemption must obtain regulatory approval (like the USA’s physician IND) before patients can receive the treatment. This frees biotech companies of the highly risky liability if the patient dies.

- Waivers or other legal protection must be in place to shield physicians from law suits.

- All people receiving the new drug agree to supply their trial data to the Dating Agency.

- Branching off patients via the compassionate usage exemption makes it possible for a rich donor to fund a trial that does not directly target their own disease but may still work because the pathologies are related. In effect, that would constitute a micro-trial alongside the main trial.

- The scheme should be open to more than one donor and supplier per disease. Several plutocrats with the same disease class, say neuroendocrine cancer, could pay into the Dating Agency for access to relevant trials. The Agency distributes the money to a number of biotech companies or academic labs who then provide drugs to the Agency. The most suitable one will be allocated to each patient.

- Checks must be in place to avoid exploitation of patients’ desperation, e.g. credit check, stage of the disease and previous treatments and remaining estimated lifetime.

As Masters points out in his article, differences in legislation in various countries add a lot of complexity. Whose burden would it be to sort that out? – The Agency’s? The trial organiser’s? The physician’s?

How would the Dating Agency itself be sustained? If it was a charity, would it rely on donations and income from charity shops? Would a percentage of each plutocrat’s contribution be used to run the Agency?

It is obvious that, despite great progress, the idea was still not fully developed, and I’m not quite sure where it stands now – 2 years later. Nevertheless, there was another campaign running to test the funding model further with an unlicensed oncolytic virus for adult brain cancer coming out of Dr David Stojdl’s lab. Again, it’s unclear how far this went. The funding for their recent trial came primarily from the Government of Ontario, Canada.

Is crowdfunding the future for experimental therapies?

I think the Dating Agency is a terrific idea! (Not so much the name though. Change the name. Please!) I may have gotten a bit lost in the plutocratic proposal, but I couldn’t really find anything that involved a crowd anymore. Is a crowd even required when one to few rich individuals can provide the necessary funds? In that case, are we even still speaking about crowdfunding?

I’m not so sure whether crowdfunding suffices to finance early-stage drug development. In the case of iCancer, many small-ish donations accrued a substantial sum, but not enough to fund an entire trial. However, it provided the publicity that eventually alerted a millionaire who chipped in the essential additional cash. Sure, this can work again. But is it an efficient process? A purely plutocratic approach provides a short-cut.

I can imagine that ‘ordinary’ crowdfunding be used to fund research at an even earlier stage. Could it fund a PhD or postdoc position? Could it help set up knowledge transfer schemes similar to the UK’s KTP? Maybe the partner organisation could be a charity or social enterprise instead of a company. The graduate would gain insights into the workings of a non-profit instead of a commercial organisation.

Benefits beyond sourcing funds and finding treatments

I love the iCancer initiative and the innovative thinking it has spurred.

Crowdsourcing gives interested people a chance to have a say in the research that receives funding. It makes scientific research more transparent to the public. It encourages an open, constructive discussion between specialists and laymen. It gives academic scientific endeavour a chance to be relevant and directly useful in real life. It raises awareness in academic circles as to what is needed, which frontiers need to be conquered.

Funding bodies regularly get flooded with applications, and assessors often probably don’t have the time to peruse each application with the attention it deserves. As a consequence, some good ideas won’t receive any funding because the application doesn’t tick certain boxes. One of my bugbears is the reliance on journal impact factors, a flawed measure of the perceived quality of a journal, rather than the originality or brilliance of the content of a scientific publication. But of course, when there is little time it is quicker to assess the average impact factor of a scientist than the quality of their work. It can be a useful metric, but demands careful interpretation. Maybe a crowd approach helps the academic world find better metrics or other ways of assessing the quality of research.

Addition after blog publication

Further Reading

Masters A, Nutt D. A Plutocratic Proposal: an ethical way for rich patients to pay for a place on a clinical trial. J Med Ethics, 2017: 43 (11). https://jme.bmj.com/content/43/11/730